Sound Diplomacy Economics: Creative Cities and Local Economic Performance

A brief empirical exercise based on the European Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor

Written by the Sound Diplomacy Economics Team: Eduardo Saravia, Adriana Rubio and Thomas Drazek

Electronic concert as part of Bains numérique in Paris - Image Credit: Nicolas-Laverroux

Key Takeaways

Workers with creative roles (creative class) are leading a change of paradigm in the global economy: Florida (2016) argues that there is a shift from an economy primarily founded on physical inputs (e.g. land, capital), towards one that is based on intellectual inputs (e.g. knowledge, creativity). As a result, workers, and entrepreneurs of sectors such as technology, innovation, arts, culture, music, design, science, and entertainment, among others are essential for policy makers to focus their attention on, because they are positively impacting the local economic growth.

A proper local context with favourable and adequate infrastructure, governance, and markets must be provided to ensure the presence of the creative class: while a city can grow in several aspects due to the contribution of creative industries, also creative industries can benefit from a city that enables an adequate context for them to grow.

There are indexes such as the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor (CCC) that show the cultural and creative vitality of territories: some authors and institutions have proposed indexes and indicators that visualise several variables that contribute towards the level of creativity in cities (e.g. talent, technology, tolerance, creative class, with other economic and social progress measures: GDP per capita, global entrepreneurship, income inequality, amongst others).

The results of our empirical model show that there is a positive relation between the amount of creative and knowledge-based jobs and the economic performance of cities: Based on the data from Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor 2019, the model shows that 34.2% of the variations of the GDP per Capita of the cities in scope of CCC, could be explained by the proportion of Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs in the cities

Whilst acknowledging the contribution of the creative class to cities, policy-makers shall carefully consider the negative effects that may arise from stimulating their presence: supporting the development of the creative class should always be accompanied by thoughtful local policies (e.g. guarantee social housing) that ensure that the wealth brought is not displacing the most vulnerable participants of societies.

The Foundation

The representatives of cultural and creative industries, such as cultural policy makers, and cultural associations, usually find themselves with limited means to advocate to find public and private resources to finance the buildup and enhancement of a healthy and wealthy setup in their local context. Nonetheless, what many stakeholders fail to grasp is the multiplier effect that the cultural and creative industries have overall on the economy.

Part of this effect is rooted in what Richard Florida (2006) describes as the “fourth industrial revolution”. He explains that there has been a shift from an economy primarily founded on physical inputs such as land, capital, and work oriented to physical effort, towards one that is based on intellectual inputs, knowledge and creativity. Therefore, the fourth industrial revolution's main characters and essences are the workers, and entrepreneurs of sectors such as technology, innovation, arts, culture, music, design, science, and entertainment, among others.

This group of workers and entrepreneurs constitutes what Florida called the creative class. Florida (2019) argues that the diversity of the members of society and the people who have creative occupations (creative class) can spark creativity in every aspect of the local economy, driving growth and overall wealth. This can be represented by a larger concentration of high-tech industries where there is a high diversity in ethnicity, age and gender (see closing note one).

Nonetheless, the existence of workers, entrepreneurs, and even businesses framed in the fourth industrial revolution does not guarantee high creativity, innovation, and wealth on its own. According to Towse (2002) it is also imperative that there is a synergy amongst these actors, enabling the creative atmosphere. But, how do the cities and territories manage to concentrate an impactful group of creative class stakeholders? The existence of a creative class in a city or territory is not accidental. It is the result of favourable conditions. This means that, while a city can grow in several aspects due to the contribution of creative industries, also creative industries can benefit from a city that enables an adequate context for them to grow. In that sense, the relationship between the city and the creative sector is not one-sided. This theory is explored by Comunian (2010), who highlights that four interrelated dimensions can determine the potential of locations to support the growth of the creative economy and, in turn, the odds of having a potent creative class:

Infrastructure: local availability of businesses spaces, transport infrastructure, wealth of residents

Governance: regulatory framework, public policy strategies and institutional interaction

Soft infrastructure :idiosyncratic characteristics such as networks, the image of a place, and the presence of traditions, and

Markets: interaction with clients and suppliers

And, how do the cities and territories manage to show the impact or effect of the creative class in the territory? For evidence, some authors such as Florida (2019) have proposed indexes and indicators that visible several variables that contribute towards level of creativity in cities (e.g. talent, technology, tolerance, creative class, with other economic and social progress measures: GDP per capita, global entrepreneurship, income inequality, amongst others).

As a result, these efforts conducted by Comunian, Landry, Florida, and other authors, serve as a way to demonstrate how investing resources in the cultural and creative industries and how the informed design of public policies of the creative sector with full knowledge of the local context and sufficient technical tools can bring more wealth to the local economy (see closing note 2). Below in this article, we will visualise a simple empirical model demonstrating the relationship between the creative class and the economic performance of the cities included in the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor 2019.

The Empirical Model and Results

The empirical model is based on the data from the European Commission's Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor (CCC) 2019, which has a sample of 190 European cities and aims to understand the cultural and creative vitality of a group of European cities vis-à-vis their peers, using both quantitative and qualitative data.

The Index (C3 index) features 3 subindexes, nine dimensions, and 29 subsequent indicators (see table). The cities in the sample have to be included in the urban audit by Eurostat and have a population bigger than 50.000 inhabitants. To be part of the CCC Monitor the city either has to have been a European Capital of Culture up to 2019, shortlisted to be a European City of Culture up to 2023, be a UNESCO Creative City or host at least two international cultural festivals and have a demonstrable engagement in the promotion of culture and creativity.

Using this data, our goal is to show that the workforce of the Creative Economy has a significant positive influence on the economic performance and well-being of the economy of cities. As an indicator for this, we used the GDP per Capita in Purchasing Power Standard (PPS). Using the GDP in this way, makes all the cities economies comparable across currencies and countries.

For the workforce of the Creative Economy we used data from the CCC on Creative and Knowledge based Jobs, which include jobs in arts, culture and entertainment, media and communication and other creative sectors per 1,000 inhabitants of the respective cities. Due to data restrictions both on the workforce and the GDP per Capita in PPS, the dataset used contained 148 cities out of the 190 in the CCC Monitor.

We ran a simple linear regression of the Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs on the GDP per capita in PPS. In doing so, we could see that the proportion of Creative and Knowledge based Jobs in the cities is a very important element in the economic performance of the cities.

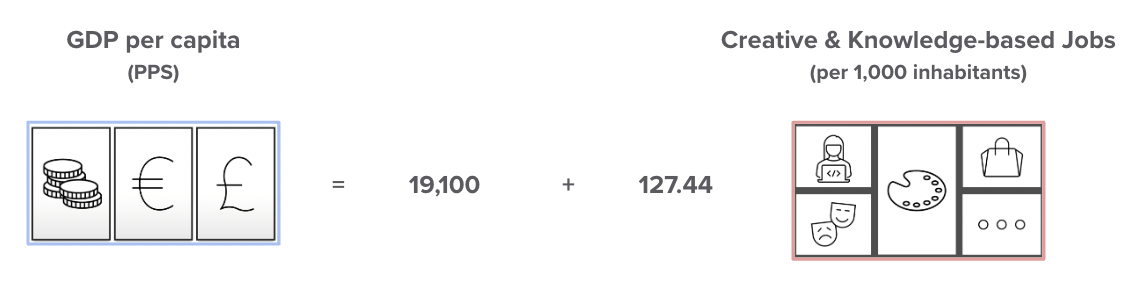

The equation that summarises the influence of only the Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs per 1,000 inhabitants on the GDP per capita in PPS is:

The equation above shows that the GDP of the cities increases by 127.44 in PPS, when the proportion of Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs per 1,000 inhabitants increases by 1. Furthermore, the regression was able to show that 34.2% of the variations of the GDP per Capita of the cities could be explained by the proportion of Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs in the cities.

Although, as stated above, we are not able to verify the causal direction between economic performance and the creative class with the available data, the model allows us to conclude that there is a strong relationship between the creative class and the behavior of local economies. As such, this exercise supports the idea that a creative city could have a positive effect on the economic well-being of a city.

This insight can promote more informed reflections and debates among cultural economists, public policymakers, and private stakeholders in cities. Furthermore, highlights the need for policy makers to create the adequate environment for creatives to be located in a city, in order to drive the GDP per capita upwards.

We hope this article continues to raise reflections and new questions in cultural economics and urban planning. Not only regarding the benefits of fostering a robust creative class in cities, but also promoting some critical reflection on other possible consequences or externalities, such as the processes of gentrification, real estate speculation, and increase in living costs of local communities.

Closing Notes

It is important to acknowledge that the following model doesn’t provide a causation assessment. This means that we are not able to state if the creative class generates economic wealth, or if the economic wealth is the cause of attracting the creative class. In line with this, Florida (2002) doesn’t argue that there is a causal relationship between the factors (creative class and the concentration of high-technology industry), but a statement that whenever there is a concentration of creative class, there is a reflection of underlying openness to innovation and creativity.

We want to point out that, as it occurs in many aspects of the economy, the presence of the creative class has, in many cases, brought other negative externalities. One of the main negative effects is the commonly defined ‘gentrification’. For this reason, we want to point out that supporting the development of the creative class should always be accompanied by thoughtful local policies (e.g. guarantee social housing) that ensure that the wealth brought is not displacing the most vulnerable participants of societies.

In the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor: 2019 Edition (Montalto et al, 2019) research showed that there is a significant and positive relationship between the C3 Index (Cultural and Creative Cities Index) scores calculated by the CCC and the GDP per capita in comparable euros. The C3 Index is the score calculated for each city by a weighted average of the sub-index scores of ‘Cultural Vibrancy’, ‘Creative Economy’ and ‘Enabling Environment’ and therefore includes all indicators mentioned in the table above. Each city's score is normalised to a result between 0 and 100. The results showed that one percent point more in the C3 Index is linked to an average of 289€ more in the annual GDP per capita. Our research expands on this idea, by looking at specifically one variable that determines the C3 Index score, the Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs.

Methodology

Before running the OLS-regression, a scatter plot was able to show a positive relationship between the number of jobs in Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs per 1,000 inhabitants and the GDP per capita (PPS). A Breusch-Pagan-Test failed to reject the null hypothesis, so there is no sufficient evidence to say that the present data is heteroscedastic. The OLS-regression was run using the sklearn package from Python. The t-test on the independent variable (Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs per 1,000 inhabitants rejected the null hypothesis, meaning the independent variable has a significant influence on the GDP per capita in PPS.

Restrictions of the model and further research

We were able to show that the proportion of Creative and Knowledge-based Jobs has a positive influence on the GDP per capita. However, there are caveats to the analysis that need mentioning.

First and foremost, the dataset used violates random sampling. As the cities in the regression analysis are all part of the CCC, they are already focused on the creative and cultural sectors as they all “have a demonstrable engagement in the promotion of culture and creativity”. Thus we can assume that the proportions of the jobs in creative fields in the database are already higher than they would be in a completely random sample. Further research should be done drawing from random cities to test the robustness of the results.

A further research topic would be to compare the contribution of Creative and Knowledge-based jobs per 1,000 inhabitants with the contribution of jobs in other sectors found in cities. This could help to classify the contributions of different industries towards the GDP in cities.

References

Bockstedt, J., Kauffman, R. J., & Riggins, F. J. (2005, January). The move to artist-led online music distribution: Explaining structural changes in the digital music market. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 180a-180a). IEEE.

Comunian, R., Chapain, C. and Clifton, N. (2010), Location, location, location: exploring the complex relationship between creative industries and place, Creative Industries Journal 3: 1, pp. 5–10, doi: 10.1386/cij.3.1.5_2

De León, I. L., & Gupta, R. (2017). The impact of digital innovation and blockchain on the music industry. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Florida, R. (2002). Bohemia and economic geography. Journal of economic geography, 2(1), 55-71.

Florida, R., Mellander, C., & Stolarick, K. (2011). Creativity and prosperity: The global creativity index.

Florida, R. (2006). The flight of the creative class: The new global competition for talent. Liberal Education, 92(3), 22-29.

Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. Routledge.

Florida, R., Mellander, C., & Stolarick, K. (2011). Creativity and prosperity: The global creativity index.

Florida, R. (2019). The rise of the creative class. Basic books.

Gordijn, J., Sweet, P., Omelayenko, B., & Hazelaar, B. (2004). Digital Music Value Chain Application.

Landry, C. (2005). Lineages of the creative city. Creativity and the City, Ne.

Landry, C. (2012). The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators. Routledge.

Montalto V., Tacao Moura C. J., Alberti V., Panella F., Saisana M., The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. 2019 edition, EUR 29797 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-76-08807-3, doi:10.2760/257371, JRC117336

Naveed, K., Watanabe, C., & Neittaanmäki, P. (2017). Co-evolution between streaming and live music leads a way to the sustainable growth of music industry–Lessons from the US experiences. Technology in Society, 50, 1-19.

Oh, I., & Lee, H. J. (2013). Mass media technologies and popular music. Korea journal, 53(4), 34-58.

Scott, A (2010) Cultural Economy and the Creative field of the City

Towse, R. (2010) Economics of the performing arts (Chapter 8). A textbook of cultural economics. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.